|

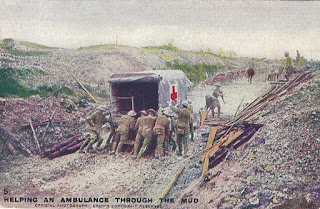

| We're in it together: American and British servicemen share a muddy moment at Yate air base in 1919 (Yate Heritage Centre) |

Similar feelings may have been aroused during the First World War, too, when American servicemen began arriving in Britain on their way to the Front, for accounts written at the time reveal that the Americans announced themselves as a fairly ebullient bunch. Among them was Corporal Ned Steel of Kansas City, who spent two months at the Third Western Aero Repair Depot at Yate, north of Bristol, in 1918.

'Twas the afternoon of April 20th when we arrived there, the first American soldiers to set foot in these parts, and we created no small commotion...Wherever we went in the next two months of our visit, the hospitality was unabounded. Talk about appreciation! Those Englishmen saw in us the reserve strength of the Allies come to deliver the knockout blow to Fritz.'

|

| The ocean liner Aquitania, which served as a troopship in WW1 |

During the crossing, Steel and his friends had been amused at the differences between themselves and the British. They gently mocked the way everything the Brits said was littered with mild curses. Even when the Aquitania's history was being explained, wrote Steel, every other word seemed to be 'bloody': 'The ship had been in the hospital service between the bloody Dardanelles and England. This was her first bloody voyage as a bloody troop ship.' The Americans also smiled at the British penchant for keeping meals simple, with Steel mimicking: 'My Gosh! Fish for breakfast?'

But the ribbing stopped when the Americans stepped ashore, to be greeted by warm and enthusiastic crowds. Perhaps for the first time, they began to understand the high price the British had already paid for the war:

'April 11, 1918 we awoke at the wharves of Liverpool. Then began our welcome in England. Ferries plying the muddy Mersey were lined with people waving handkerchiefs at us. And when we had landed a little later and were marching to our train through the uptown district of Liverpool great crowds along the way watched us. Crowds, mostly of women, they were - and rosy-cheeked girls. Young men were conspicuous by their scarcity, in fact were almost a minus quantity. It came to us forcibly then that England was doing her utmost in manpower, and some of our prejudice vanished.'

Steel appears to have been charmed by his rail journey south to Bristol:

'With a squad to each compartment on our funny looking coaches we started across "Merry Old England". The dinky little engine quite surprised us with its speed. What a beautiful country it was...green green grass covering every inch of untilled ground...stone walls...everything clean and tidy...for once the Californians were mum.'

He noted how few level crossings there were, with the train more often going over bridges or under roads: 'Only once in England did we see a wagon road intersect the railroad's right of way and then strong gates of iron shut out the traffic and the watchman tended them as the train went by.' At Bristol the men changed trains for Yate ('a town with one street').

|

| Men of the American Air Service form a 'propellor' at Yate air base in August 1918 (Yate Heritage Centre) |

In the workplace, Steel observed the different manner in which the two nationalities set about their jobs: 'The common impression among us in regard to Tommy was that he was slow but thorough. "Swinging the lead" (taking it easy) was quite universal in the [work]shops when the flight sergeants and officers weren't around. When it came to turning out first class products, however, Tommy was there'.

Meanwhile: 'Tommy was penning his impressions of us: how Sam carried himself as tho' he owned the world, was free-and-easy and took no rough talk from his non-coms [non-commissioned officers].'

Steel concluded: 'When the history of this war is written, let it be remembered that the American Aviaition Squadrons stationed in England did their bit by strengthening the hearts and wills of their English cousins at an hour when the war looked darkest to them.'

Confident words indeed, but after a few weeks in France things would often look rather different to the fresh young men who arrived from America with bags of enthusiasm but little experience of trench warfare. Such a caution were sent home by George Swales, one of the first American soldiers to arrive in France whose his story is told in my book Letters from the Trenches. In a letter to his wife he wrote:

‘I hope the Yanks don’t think they are going to have a walkover for they are in for a surprise. I thought I had a pretty fair idea of what it was and I expected it to be rough but it’s worse than what Sherman [an American general] said war was. It will take some of the swank out of them before they are two weeks in the trenches.’